Wan Smolbag’s new play, Kaekae Rat, is a broadly acted but subtly layered allegory of life in modern Melanesia

Originally published in the Vanuatu Daily Post

‘Really,’ asks the King Rat, ‘how exactly are rats and humans different?’

Out of that simple spark rises a complex allegory of honesty and deceit, selfishness and survival, all found in the least likely places. Wan Smolbag’s newest play—one of three in this year’s season—is the most ambitious yet in terms of its story-telling. Director Peter Walker says the play has a bit of a Cinderella quality to it, but here, it’s the rats are riding in coaches.

Rats and humans have always lived together, we are asked, so how, exactly how do they differ? They have leaders and followers; they all live and thrive surrounded by refuse; they squabble and vie incessantly; and they lust and love—and confuse the two—just as (in)constantly.

So why is it such a big deal then, when the King Rat becomes obsessed with Veronik, a still-pure flower of a girl, living in semi-squalor in Port Vila? At turns charming and menacing, he and his cohort are willing to wheedle, extort, con and coerce anyone in order to win her hand. Despite King Rat’s constant moans of frustrated desire, the solution turns out to be a simple one: Just find enough money to satisfy the girl’s so-called parents, and nothing else matters. Not even the wishes of Vero herself.

The plot writhes from one episode to another as rat and human natures try to come to terms, and as their mutual motivations are unveiled, it becomes increasingly difficult to answer King Rat’s question. And yet… and yet, as Vero’s younger brother candidly confesses, ‘who wants a rat for a brother-in-law?’

Writer Jo Dorras’ scripts have always eschewed happy endings and pat answers to anything, but her story lines are often drawn with an almost fatalistic directness. If we can’t see how the play is going to end, it’s only because we’re not ready to admit it to ourselves. But although the stakes are just as high here as in her other scripts, and the moral landscape is just as bleak, this play’s structure is more playfully built, and the forces are more finely balanced.

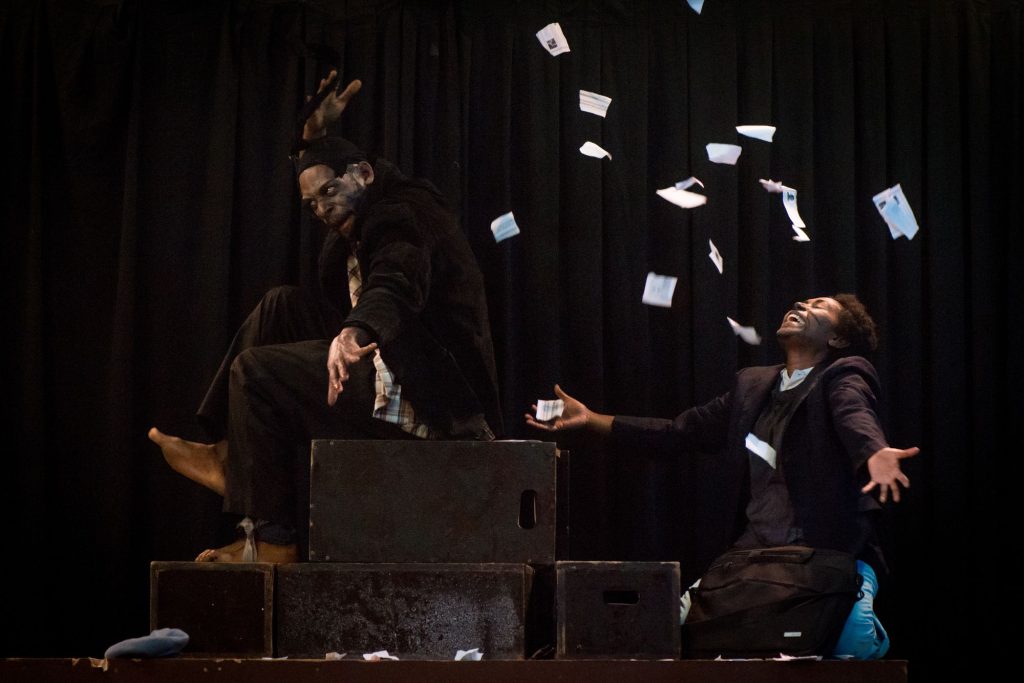

This wouldn’t be a Wan Smolbag play if it didn’t feature the simple, ingenious theatricality that lies at the core of the company’s ethos. They are, after all, named for the small bag of props that was all they used in their early days. The set is spare and appropriately garish, and still provides room for top-to-bottom, end-to-end theatre. The actors revel in their space.

The comedic, chaotic pulse of daily life in Vanuatu is another thing that one comes to expect from Wan Smolbag, and this time it’s delivered in spades. Some of the character and casting choices are nothing short of inspired. Historically the company has avoided child characters because of the difficulty and demands involved. But this time, they’ve created some of the most rewarding bits of theatricality ever to emerge from this stage.

Albert Tommy and Michael Maki, each fully-grown and sporting full beard, play Jalz, a darling, naïve, infinitely suggestible boy of about nine years. The tension between their appearance and their astonishing appropriation of the tics and tropes of a young boy draw gales of laughter from the audience. By the time they are called on to unveil the seeds of venality in human nature, they are utterly believable.

And in their heart of hearts, what actor wouldn’t want to play a rat? We revile them, but they remain fascinating for their cleverness, their adaptability, their ability to squeeze themselves into any space, and the utter refusal to leave us alone. Danny Marcel and Richie Toka share the role of King Rat, a nasty, ruthless, obsessively lustful and perversely seductive creature who cannot accept that Rat is in any way less than Human. Though each actor takes his own road to ownership of the role, they are both a pleasure to watch.

Equally enthralling is Olfala Rat. Henchman, hatchetman, bagman, supporter and sycophant, this creature lives by its wits—which is pretty much the only way a rat can manage to grow old. Once again, Peter Pakoa and Helen Kailo take very different roads to owning this character, but each is enthralling. It’s especially nice to see Mr Pakoa back in a key role after years as a stalwart in the theatre company.

There’s no such thing as a ‘normal’ character in a Wan Smolbag play; every single one of them is remarkable in some way or other. And it’s a shame, really, to have to leave out a single name when praising the riotous, hilarious, satirical and achingly honest portrayals that grace the stage. There is not a false note in the night, from Edgell Junior’s charming, soulless rogue of a father to the unnervingly accurate severity of both Evelyn George and Joyanne Quiqui as the mother… all the way down to a charming, hilarious vignette from of aging Rastaman at a public meeting.

Somebody once said of a great actor that he would draw the audience’s focus even if he were third spear-carrier from the left. The same can be said of Wan Smolbag’s theatre company. Every single one of them knows exactly how to tease and squeeze the audience’s attention, pushing, prodding and snatching focus back and forth amongst themselves… and out of the anarchy, they weave a spellbinding allegory of life amid the refuse of living.

Who wants a rat for a brother-in-law? Come to the play and see.

Wan Smolbag’s Kaekae Rat runs on some Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays through the rest of May and June in Port Vila, and for a number of dates in Luganville. Check the posters around town for details, or visit the Wan Smolbag Facebook page. Tickets are on sale in front of the Post Office. Reserve early because shows usually sell out.