Over the weekend, I watched Spotlight, the Academy Award-winning film about a team of investigative journalists who uncovered a story about systematic child abuse and how their society’s institutions protected the abusers. It’s an agonising—although beautifully told—story about daring to speak the truth.

But I was on the verge of jealous tears over the resources the Boston Globe lavished on its investigative reporters. In one scene, the newly appointed editor meets with the Spotlight editor and is told that this team of five journalists(!) typically take up to a year to research, investigate and write each story series.

As an old Yorkshireman famously said: Luxury.

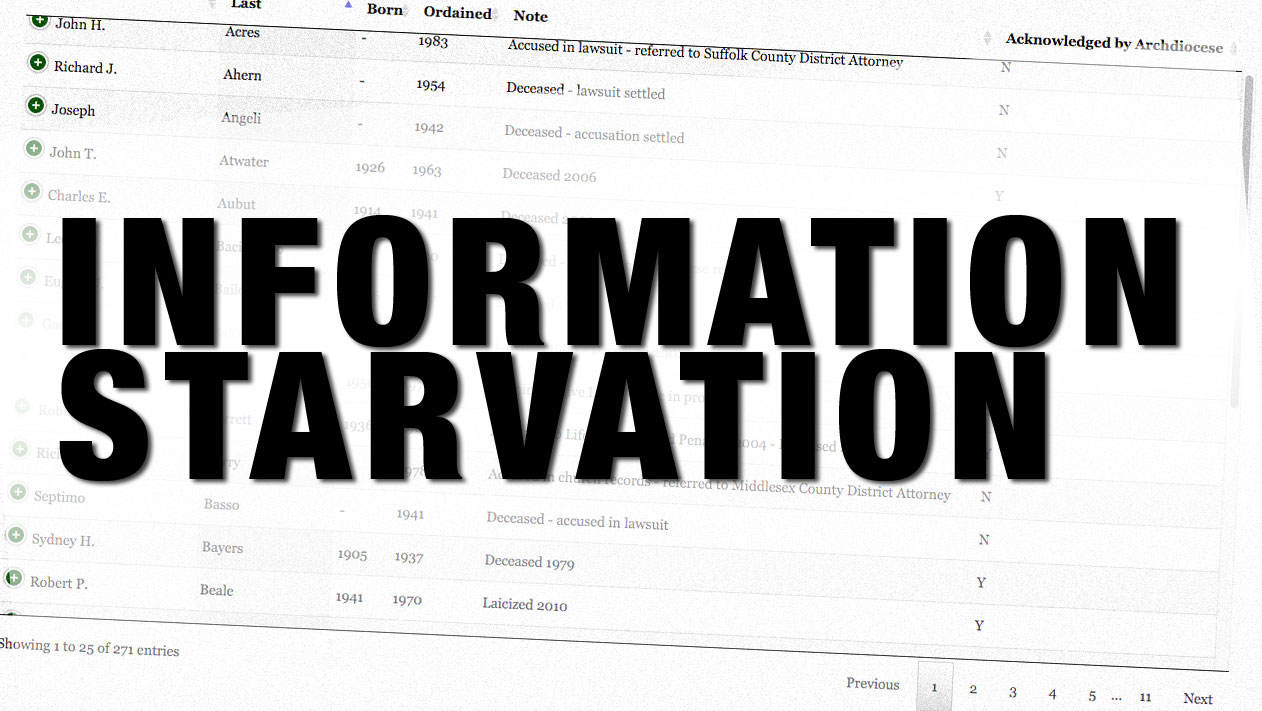

The vast majority of the incredible run of stories Spotlight published on the Boston child abuse cover-up (200 in a year!) were records-driven. Yes, there were tons of interviews and mile upon mile of plain old legwork. But without documentation, their pieces would have been little more than hearsay, and the stories would likely never have run.

Everyone who’s spent any time at all thinking about media in Vanuatu, or anywhere in the developing world, for that matter, will instantly recognise that our greatest challenge is not the lack of investigative reporters, but the lack of solid, verifiable information.

Records, records, records. That may sound boring, but it’s the heart of who we are. Think about it: A complete, up-to-date and manageable voter registration list would likely have made it possible for thousands of new voters to be registered in time for the snap election earlier this year. Good records make good voters. Read more