Decentralisation and federation allow developing countries to be masters in their own digital house

The impact of social media on developing countries has received little attention in the popular press, with the exception of horrendous events such as the attempted extirpation of the Rohingya people in Myanmar.

These impacts are real and cannot be overstated.

Here in Melanesia, societies are at once more susceptible to gossip-driven scares and even mob behaviour, and more resilient in the face of it. It’s easier to set people off, and it’s easier to spread common sense.

The simple reason is that we are closer together. Your neighbour may drive you round the bend from time to time, but go far enough round the bend and you’ve done a circuit of the island. They’re not going anywhere, and neither are you. That’s the historical truth, anyway.

Social media has made the public sphere vastly larger and noisier, but the same rules apply, more or less.

Women are harassed, abused and faced with physical harm not just by their family and neighbours now, but by the entire online population.

Gadflies and conscientious objectors face opprobrium not just from the chiefs and other people of rank, but from masses of virulent and often anonymous attackers.

And anonymity/pseudonymity is a novelty that many struggle to come to terms with. While it’s freed the tongues of many who felt constrained from speaking before, a significant minority of them have used that liberty to behave horribly to others.

But in the midst of this chaos and rancour, a fascinating thing has happened: People are learning to moderate debate in real time. The pattern here in Vanuatu typically runs like this:

A person attacks another, making allegations that might or might not be true. One side piles on, either in concert with or in reaction to the original poster. Generally speaking, the conversational tide runs almost entirely in one direction, with few people showing the gumption (or the chutzpah) to gainsay the rest.

But then, slowly and sometimes softly at first, the first words of moderation appear. Before long, others find it in themselves to support this view or to supplement it with their own objections. Eventually, a trend begins to come clear, and comments with widely divergent views either peter out or are drowned out.

The process can sometimes be outright vituperative, sometimes not. Sometimes the right answer is found, sometimes the wrong one is reinforced. But even in the worst cases, where we see incitement to violence, to burn homes, expel people, exact vengeance or pour shame on a person or group, there are few if any instances of people actually acting on them.

In cases where people actually have done reprehensible things to one another, they were seldom discussed or organised over public social media channels. Slut shaming in cases of perceived infidelity are the one glaring exception.

The flow of discourse resembles nothing so much as a village meeting. I’ve attended more than a few, and they tend to follow the same pattern. If you walk in cold to the early stages of a contentious meeting, it can sometimes feel like the only possible outcome is open conflict. The tension is often palpable.

But as it unrolls, tempers begin to subside, and more nuanced and reasonable arguments begin to emerge. By the end of it, more often than not, the chief is able to find a ruling that will carry the room, and people part with handshakes and a sense of having accomplished something.

(I’m painting with a very broad brush here, so forgive the massive elisions in that description.)

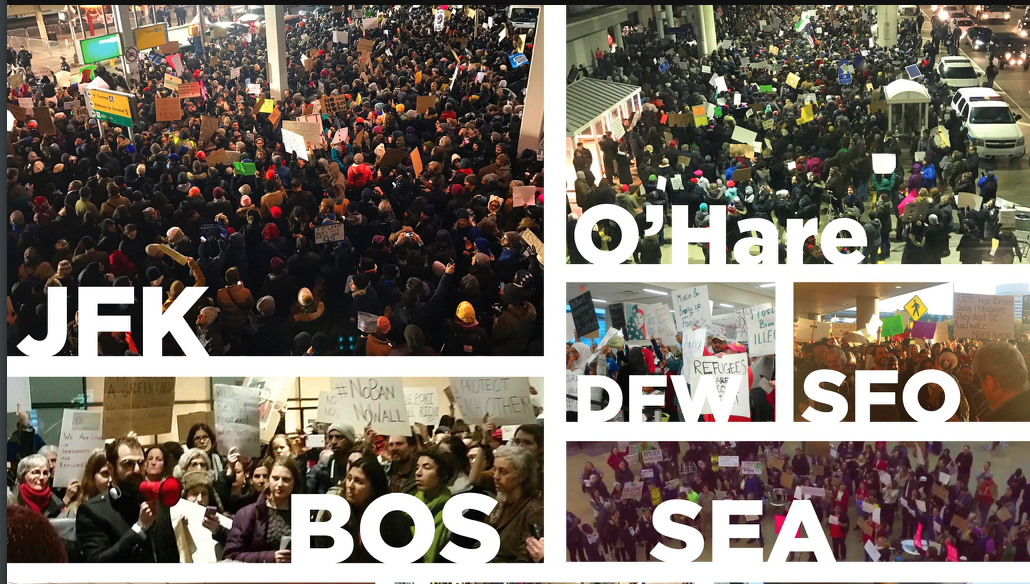

We’ve been able to resist of the worst conspiracy mongering here. Even when Indonesian state actors conducted a Cambridge Analytica-style campaign to undermine confidence in the government of the day, the effect was minimal.

But it didn’t stop until high-level meetings were held with Facebook executives. Faced with a Prime Minister fully prepared to regulate them or see them leave the market immediately, they did the right thing.

That was only one victory among literally thousands of attempts. Dozens of user reports concerning this influence network received no response at all. Hundreds of reports of incitement and hateful comments went unheeded. In rare cases where a response was received, Facebook’s so-called community standards allowed imagery and language that were shocking to us—and to any thinking, feeling human. Images of dead and dismembered bodies, sexualised and clearly brutalised children… the list goes on.

Then, adding insult to injury, imagery of people in kastom dress were banned, because apparently a nambas or a nipple is beyond the pale, even though they scarcely raise an eyebrow here.

The push here became strong enough that Facebook’s head of Global Connectivity Policy met privately with the Prime Minister to dissuade him from moving ahead with a proposal to require them to register as a local company.

The Prime Minister’s rationale was that Over The Top services such as Facebook should be required to contribute to our Universal Access Policy, the same way all local telecommunication providers are.

But another, and I believe more compelling, argument is language. There is no business case for Facebook to provide support for Bislama, Solomons pidgin, Tok Pisin or any other of the thousand-plus languages in the Pacific islands. It’s just never going to happen.

The only way these languages—and our cultures and societies—get the respect and support they deserve is when social media networks become our networks. Without ownership of the content and of the management service, we are not masters in our own house.

Technology generally and social media in particular can accurately be described as a (re)colonising force. The imposition of standards, expectations and requirements that are not only foreign and new, but often beyond the capability of a great many people here doesn’t just bring development potential. More to the point, they’re largely impossible to alter to fit the local context.

Technology and social media are just as subversive as they are liberating.

And while our societies are generally better at self-regulation, we’re hardly perfect. The suffering and subjugation of women in the Pacific has always been a matter of concern. Social media adds slut-shaming, stalking, coercive talk and mobbing to their already tremendous burden.

The inexperienced have often been victimised by cons, scams and schemes, but they have only grown in proportion since the advent of the internet and social media.

Decentralisation and federation of social media services doesn’t fix everything. It doesn’t provide any guarantees at all. Except one: if we screw it up, it’ll be our screw up, not someone else’s.

And that’s what decolonisation has always been about.