This week’s Post Courier debacle, in which a lurid front-page spread purporting to show Asian sex workers in a Port Moresby nightclub was shown to be false, is only the latest journalistic misstep of many across the Pacific islands.

Originally published on the Pacific Policy blog.

This week’s Post Courier debacle, in which a lurid front-page spread purporting to show Asian sex workers in a Port Moresby nightclub was shown to be false, is only the latest journalistic misstep of many across the Pacific islands. As far back as 2012, accusations of plagiarism have been levelled at the author of the article. The evidence in some of these cases is compelling.

In this particular case, the paper published a front-page correction the very next day, admitting that the writer had published the photos without knowing their actual provenance. The very same cover featured another couple of photos of Asian women with their eyes blacked out, ‘reluctantly supplied’, they said, by one of the sources of their stories on sex workers coming to work in Papua New Guinea.

While the Pacific Freedom Forum welcomed the prompt correction, social media response was less forgiving. A large number of commenters decried the entire week-long series, claiming that it was a transparent ploy to sell papers on the back of public prurience.

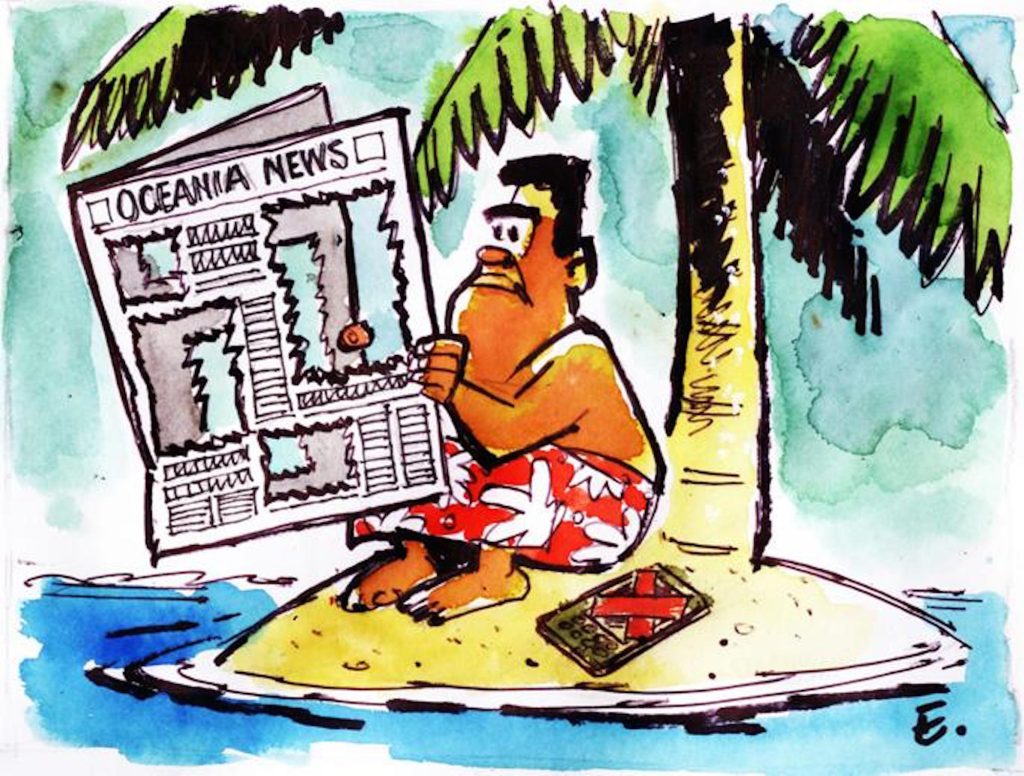

The readiness of media professionals throughout the Pacific islands to treat untested sources, hunches and even rumour as reportable is a phenomenon that needs to be recognised and addressed. It’s difficult to measure the civic importance of having reputable news services, but it’s fairly safe to say that fewer Pacific islanders than ever see their media organisations as truly authoritative.

Complaints are rampant in social media and elsewhere about the ability of media services to reliably and objectively report ‘all the news that’s fit to print,’ as one masthead famously stated. State-owned television and radio are determinedly non-confrontational. Even private-sector media are fighting what seems to be a rising tide of political and financial pressure.

It sure doesn’t help that elsewhere in the world there are fewer and fewer examples to hold up for emulation.

The Post Courier itself is owned by News Corporation, made infamous by the UK phone hacking scandal, and the rather blasé attitude toward truth shown by some of its properties. Mr Murdoch’s possessions are, of course, hardly alone. Just last week, the Telegraph’s former chief political correspondent publicly accused the tory institution of perpetrating ‘a fraud on its readers’ for its unwillingness to cover the revelations concerning HSBC, one of its largest advertisers.

Mr Oborne lamented the necessity of publicly shaming his former employer, but claimed, ‘It might sound a pompous thing to say, but I believe the newspaper is a significant part of Britain’s civic architecture.’ It is too important, in short, to be permitted to fall, unremarked, so far from its ideals.

Agencies designed to foster ‘responsible media’ end up working more to subvert it than to sustain it.

Arguably, Pacific societies have no such ‘civic architecture’ – or at least, no significant history of supporting and even fostering gadflies in their midst. Quite the opposite, in fact. So it should come as no surprise, perhaps, that agencies designed to foster ‘responsible media’ end up working more to subvert it than to sustain it.

Fiji’s case provides the most compelling example. The notorious Media Decree of 2010 created what some have wryly called ‘collaborative journalism’, in which the state plays a direct role in policing journalistic activities and –purportedly– ensures positive and harmonious social development. The reality has been something less than that. MIDA’s director, Ashwin Raj has been laughed at for ‘defending the indefensible’ (i.e. the regime’s conduct in controlling the media). When, the biter bitten, he became the victim of the very same arbitrary enforcement of the law he claimed did not exist, few expressed sympathy.

Quoth one commenter:

If that honesty, fair criticism and transparency existed under his MIDA rule, there is little likelihood the police would have tried to get away with the abusive behaviour he alleges occurred to him. But no, he has helped to create that very same culture of impunity in public office about which he now wishes to shriek….

More recently, Mr Raj has come under fire for allegedly circumventing MIDA’s own processes and procedures. Ironically, he was censured for issuing a judgment against a column –which, to be fair, was composed of little more than schoolyard taunts– in the Fiji Sun. This paper has been characterised as the Bainimarama government’s ‘lapdog’. Some hope that these most recent events will finally convince the powers-that-be that a caged media establishment is actually no better than a free one.

To be fair, the fourth estate has always lived on the edge of reputability. It got that name during a period when shameful, downright pornographic libels were being published almost daily against the French queen. The partisan press of 19th Century America was shamelessly biased, and outright vulgar in its prejudices. At the height of the Hearst empire, the ‘yellow press’ were the rule, not the exception.

The pendulum swings two ways, however, and the excesses of the partisan American press brought about a reaction that, in its heyday, represented the highest ideals of bearing witness to history and speaking fearlessly in defence of justice. Pioneers such as H.L. Mencken built an institution in North America that allowed Cronkite, Murrow and others of their generation actually to shape the course of events.

With the rise of the Murdoch empire, though, western journalism has fallen far from this ideal. Back in 2002, one bitter ex-journo said to me that, ‘the moment the bean counters moved into the head office: that’s when reporting the news became secondary to selling copy.’

History seems doomed to repeat itself.

To be fair, there are a number of shining lights in the Pacific pantheon. This blog has been graced by regular contributions of Kalafi Moala, who has done much to contribute to Tonga’s recent rise in the freedom index. Giff Johnson’s work in the Marshall Islands meets –indeed sets– the highest standard of journalism. Elsewhere, the Solomon Star has managed to maintain its reputability under trying circumstances. Political gadfly Marc Neil Jones, who has been ‘assaulted, deported multiple times and jailed’ since he started his Vanuatu newspaper, will be retiring at the end of this year, but his legacy lives on.

If anything, though, these salutary examples only highlight the problem when, in spite of numerous and serious accusations of journalistic misconduct, writers like Gorethy Kenneth are not only left unscathed, they are promoted to the highest rank.

Here in Vanuatu, a burst of civic fervour and renewed journalistic activity has not led to a concomitant rise in standards. One newborn newspaper recently published an encomium to the ‘late’ West Papuan independence leader Benny Wenda. (He seemed fine when I saw him a week or so later.) So this week’s announcement of the creation of a self-regulating media body seems to me to be a mixed blessing. I worry that while it may stave off external efforts to quench free expression, it will do little to foster it.

Following the most recent criminal assault on Daily Post publisher Marc Neil-Jones, the rival newspaper devoted its front page to a defence of the man ultimately convicted of the crime, and the then-chair of the media association spent more time bloviating about ‘responsibility in media’ than denouncing this clear assault on a free press.

We talk at length of the need to curb corruption, laxity and self-interest in the public sector. It seems to me that we would be well served to take a close look at the reputability of those mandated to create, safeguard and preserve the public record.

Integrity comes at a price. More of us need to be willing to pay it.