[Originally published in the Vanuatu Daily Post]

Every morning I walk the 150 metres from my house to Freswota road beside the cemetery and wait for a bus. I always avoid looking at the nearest corner. For the first few weeks, I didn’t understand why that part of the graveyard unsettled and distressed me so. Then I realised what it was: The plots were half the size of normal ones. This is where they bury the children.

Every morning I walk the 150 metres from my house to Freswota road beside the cemetery and wait for a bus. I always avoid looking at the nearest corner. For the first few weeks, I didn’t understand why that part of the graveyard unsettled and distressed me so. Then I realised what it was: The plots were half the size of normal ones. This is where they bury the children.

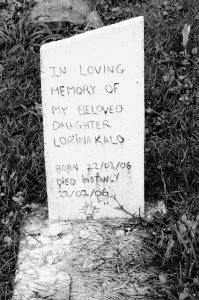

I’m going back there today to stand by two close friends as they lay a little box into the ground.

The parents are part of a young and promising generation of professionals. They each lifted themselves up by their bootstraps, worked hard and, little by little, rose from menial positions to shoulder real responsibilities. They met one another, built a solid foundation of love, respect and stability, and then began their family.

The baby died in childbirth. Her death was entirely preventable. Her life could have been saved a dozen times over in the days before the crisis.

There are excuses enough for everybody, if we want them. For the undertrained and overburdened staff of the maternity ward, who handle literally dozens of deliveries every day, and who do so in an overcrowded, dilapidated building using a hodge-podge of outdated and insufficient equipment. For the doctors who, despite their deep commitment, are left with no choice but to ignore the cries of some in order to sleep enough that they’re not useless to everyone else.

But I don’t care about excuses right now. I don’t care what the reasons are. I want to carry that little box with its heart-crushing cargo into Parliament and lay it on the floor. I want to tell the politicians: These are your numbers. This is your no-confidence vote. This is the product of your waffling, your picayune intrigues and faithless manoeuvrings.

I want to carry it into the offices of the civil service and tell them: This is the price of your complacence, your early knock-off and late arrival, your angling for the car and the subsidised house, your commitment to doing the minimum or less, your willingness to be seduced by the intrigues and venality of those in power.

I want to show it to the donors, and say: This –right here– is your bloody Millennium Development Goal. This is what you get for slipping into to that back-of-the-mind conviction that being wealthier and better educated makes you somehow superior, more valuable than those you claim to serve. You so-called experts who can’t string two full sentences of Bislama together, who have never spent even half a day in the muddy lanes of Ohlen or Manples Mango.

You wealthy expatriates who have the money to extricate yourselves entirely from the health and education systems, content to make it someone else’s problem.

You so-called investors, who would rather pay for a boatload of indentured workers than support the local people. Who call Ni Vanuatu ‘lazy’ because they won’t work 6 or 7 days a week for a pittance. Who cheat on wages and VNPF and VAT contributions, who take every shortcut available up to and including bags of money for the Minister, then cry in your beer about the weakness of the State.

And all you high-minded activists hell-bent on saving the nation from the chimera of the WTO because it’s easier to slay dragons than to take on something as mundane as planning, staffing, training and equipping a health system. Who can’t even conceive of a health system at all. Who bemoan the influx of advisors and donor money but who can’t begin to express how to actually, practically, fix things.

All you wittering elite who somehow think that passing inane platitudes and slogans back and forth on Facebook is how we fight for justice.

You holy rollers preaching intolerance, trying to remain impervious to change, casting aside your own children rather than accepting that the world is not what it was, that it was never what you claim it was.

You holy rollers preaching intolerance, trying to remain impervious to change, casting aside your own children rather than accepting that the world is not what it was, that it was never what you claim it was.

You voters who think of your MP as nothing but a candy jar, a well to dip into whenever you need school fees, wedding or funeral expenses. Who will bicker and squabble endlessly over the MP allocation but never once ask him, ‘What have you done for your country?’

You people who can’t see beyond your own yard, who in your petty jealousy would rather drag down a successful neighbour than cooperate for the common good. Who would rather spite yourselves than allow another to profit. Your family alone won’t repair the road. Your family won’t build the new hospital wing.

And yes, you well-intentioned few who really try to care, who live life with your head up and your eyes forward, who try to get things done in a culture fraught with complacence and disaffection. Even you.

Even you. Because every time the future is torn away, banished to a little box, we have to know we’ve failed. We have to see how we’ve failed. We have to see it.

The couple at the centre of this tragedy represents the very best of Vanuatu: Young, intelligent, ambitious; mindful of tradition while they help define the nation’s future. They weren’t short-changed or tricked or cheated. They got the best treatment the country had to offer, vastly better than what they might have received in Lenakel or Lolowei or Sola.

But it wasn’t enough. Vanuatu gave the best it had to this couple, and it failed them. It wasn’t enough.

I don’t have any answers, because there are no simple solutions. There’s no lynchpin to unlock this mess of distractions and details and make everything right. All I know is that none of us have done enough. We need to see past the policies and principles and simply act.

Maybe all we can do is find one thing and fix it and move on to the next. I don’t know. But I do know this: We need to stop obstructing others with our jealousies and petty, small-town politics. We need to stop obsessing over who is Right and who is Wrong and get to bloody work.

I don’t care who you think you are or what role you play; you have to do more.